How Policies Can Invert Democracy

Up until now, in the context of recent modern history (circa 1933 – to date) the BY spaces have been known for the sum of their problems, not for their abundance of hospitality, gift-giving capacity or associational life. Nor have they (citizens) been viewed as the primary inventors of a preferred future for all and the planet. In part, the reason is that consumer society obscures the small, local everyday exchanges that so delicately, so imperceptibly knit us and our well-being together. The popular culture renders that which is most abundant invisible.

In equal measure, political policies have inverted democracy in four ways. First, the role of citizens is now defined as what happens after policy makers, politicians and professionals have completed their expert functions. I have argued for the opposite: the roles and functions of public servants should be defined as what happens after citizens complete their irreplaceable work. The state’s civic professionals should ensure they provide support to citizen’s efforts and then find a place as an extension of civic capacity, instead of a replacement for it as they often currently are.

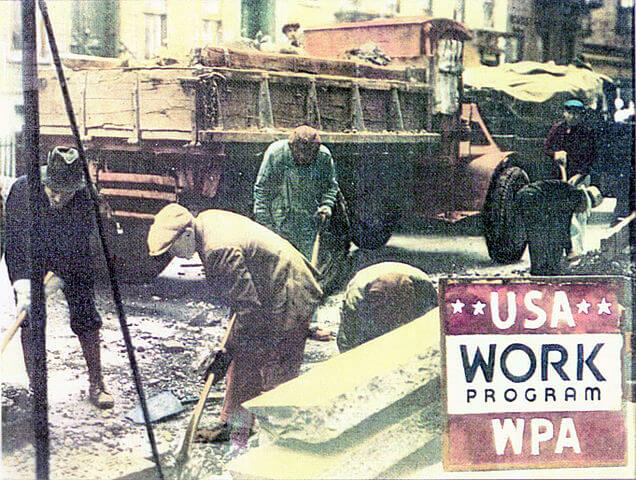

Second, modern societies since the New Deal have defined helping as relief, rehabilitation, and latterly advocacy and, even then, almost exclusively within the parameters of programs and services. The modern shift that takes the state closer to a civilised role and duty towards its citizens has been progress. However the same formula for concentration of power is carried out. Modern citizens are relieved from fear of state subjection but placed in the position of institutional dependency. Modernity takes the citizen from angst over misuse of state power to anxiety over abandonment by the state as funding priorities change.

Third, the units of change up to now have been limited to two: individual behavior and lifestyle change, and institutional expansion. Both of these change measurements come from top-down and distant perspectives, which act upon social policy of managing deficit behaviours and look to use deficit-based planning that bolts on costly extensions to established institutions. This view fails to recognize a third more essential unit––the neighborhood or village––as the primary unit of change.

Fourth, regardless of whether they are Left or Right leaning, in ideological terms policies are in accord with the belief that people who are economically isolated or negatively labelled cannot be trusted to self-determine their futures or navigate life’s vicissitudes. The only points of disagreement among them is as to whether such people should be rescued or policed, and by whom. The Right supports business interests, through privatization of services, while the Left advocates for the human services side of the economy as deserving pole position in helping the “needy.”

These are in fact economic, not political debates, which mostly fail to relocate money and authority into the hands of the people who are being supported. Instead, the lion’s share of resources goes towards maintaining the institutional infrastructure and salaries of those who are providing the help. This is to say, in economic terms, that the helping institutions need people’s needs, often more than people need their services. This debate reduces human beings to bundles of eternally defined deficits, wilfully refusing to recognize them as citizens, with invaluable contributions, to be liberated in rekindling democracy. For those receiving such help, one wonders how much of the salaries of those who are helping them in this way would they use to purchase similar services?

Cormac Russell

Klaus D Pluemer

Good points, Cormac! But a society is more than bundles of neighborhoods or villages.

All what makes a modern society attractive is the underlying process of civilization (Norbert Elias) that creates a civil society. In short there is no stste and its institutions on one hand and the citizens or people on the other hand. The interaction of all of us creates the so-called system. This has to be understood as a prerequisite to change it through mission-oriented innovations. I like this term by Marina Mazzucato from her brilliant book: ‘The Value of Everything’. The best what I have read since years about political economy and distinction of value creation and value extraction. I think, the biggest mistake we (the people) make is the externalization of the complex outcome of our interactions as system and define it as our opponent.

Peter Evans

Klaus good points about the advantages of a civil society but at the risk of sounding like a socialist, that’s more an ideal than a reality.

I know you’re giving the quick summary version, but to assume that situation exists in Britain (for everyone, in the same way(s)) ignores differences in peoples’ ability to influence or control the offices of the state, how state resources are deployed and so forth.

The state is neither entirely a part of nor seperate from “the people” (to use a nebulous phrase, but I want to avoid citizen as my point is about that role being constrained).

It also ignores barriers that are in place, and can/have been entrenched to ensure and perpetuate the differentials in influence etc. Conflicts of interest can and do manifest in and through the state.

Despite the “one nation” ideal we are not “all in it together” in the same ways when it comes to the state and our relationship to it.

Finally, remember that in communist societies the state was supposed to be both for and of the people – it was just more starkly apparent that it wasn’t (and even that it must be said, was from the outside until well into their rule…).

Civil society is a better solution definitely, I don’t mean to say it’s like for like, but just that doesn’t entirely remove issues and tensions between bureaucracy and democracy.

Cormac Russell

Thanks Klaus, great points. I agree with you and to clarify, I’m not arguing either other, I’m arguing for the foundation being citizen-based and more localized not red tape and globalized. Currently it’s red tape and technocrats first, citizens and communities and our environments and cultures second. That’s the wrong order. The loss of trust in institutions which hatched from associational life but have become dissembled from society will be stemmed when we reintroduce the practices of ‘service’ and open public discussion as to what we want our world to look like while respecting divergent views. For some that can be spoken about at state and global levels, for most though it will have to happen closer to home and then radiate outwards. It’s a question where to start and how to deepen the conversation to include as many as possible. We must at all costs avoid Levisthans and Philosopher Kings or more populism.

BW,

Cormac