What’s the Story? Post-Truth Politics and Vaccinations

” People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” – Maya Angelou

Here’s a little joke to start:

One day a computer scientist wondered whether a time might come when computers could think like humans. After many years of studying the available data, his results were proving inconclusive. As a last resort, he decided to consult his own very sophisticated computer. And so, he typed in the question: “do you think you will ever think like a human?” An hour or more past with no response, then the cursor flashed up on the screen and the following words appeared: “that reminds me of a story….”

We are creatures of narrative, we step out of one story only to enter, into yet another. Even our data is layered with stories. That’s why if we are paid to support people it is so essential that we find more effective ways of enabling them to shape their own stories and the common stories of their shared lives, instead of trying to convince them of ours.

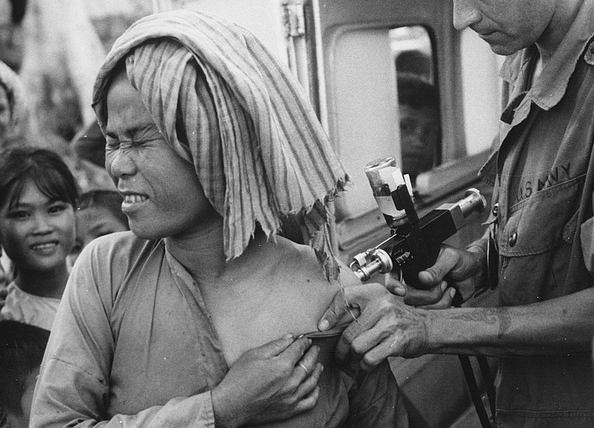

Tara Haelle from Parents Magazine in reviewing “Why {some} Parents don’t vaccinate” notes that data is not enough to convince all parents to vaccinate. On a separate but related point, she notes that in some instances professionals are not sharing the data in its fullness because they are anxious that parents may misconstrue the evidence and make the ‘wrong’ choices. The ‘vaccination’ example is emblematic of an ongoing dilemma at the heart of how some experts communicate with lay people, indeed I would argue it‘s a dilemma at the very heart of current versions of democracy, insofar as it positions experts in a privileged/superior position in relation to uncredentialed citizens.

Three kinds of knowledge: Expert, Private and Public

The Greeks believed that through processes of public deliberation (this includes everyday over the garden fence deliberation as well as Public Deliberative Forums) citizens produce their own practical wisdom or knowledge, distinct from that kind of knowledge that can be produced by experts or specialists with recourse to factual evidence. This practical wisdom which they called phronesis, was also seen to be different from personal judgement, it was instead a sort of collective ‘knowing how to act’. Appreciating the difference between expert, personal and collective knowing, while avoiding the temptation to pit one against the other is at the heart of understanding what’s going on when for example parents don’t vaccinate.

When I look at what is happening with issues like child vaccinations what I see is that the relationality between expert, personal and collective knowing is out of kilter. Therefore, the solution is to figure out how to get these ways of knowing back in right relationship. Of course, this matters at a number, of social, political, economic and environmental levels, so my commentary is not unique to public or population health.

Post-truth Politics and the rise of Fascism

With evidence that Fascism is on the rise; that populist propaganda and post-truth politics will gladly throw the accusation of ‘fake-news’ at whatever version of reality they dislike, regardless of the evidence or even common-sense, there is an incredible urgency in learning how we can better align these three ways of knowing.

| Expert Knowledge | Collective Knowledge | Personal Knowledge |

| Specific/Specialised | Multifaceted | Personal opinion |

| Exclusive | Inclusive | Subjective |

| Emphasis on excellence & accuracy | Emphasis on applicability & practical in wider community | Emphasis on ‘how it impacts me, my family & friends’. |

| General | Particular to us | Particular to me |

| Scale up | Local (scale down) Small is beautiful | Self/Family/immediate network |

| Efficiency | Responsiveness to wider community mindful of varying support needs | Responsiveness to self/family/immediate network |

| Three domains of Knowing, developed by Cormac Russell, 2017, CC BY SA 4.0 | ||

All three ways of knowing and judging are important. Problems arises when:

- We use the wrong ways of knowing relative to the context i.e. some decisions require personal discernment, others are matters of public deliberation (citizens weighing up what people hold dear and working through the trade-offs), and yet other decisions are clearly contingent on recourse to the scientific facts. Of course, life is not that clear-cut, and so these ways of knowing are often interdependent and can and do therefore overlap in mutually reinforcing ways. But sometimes one crowds out the relevance of the other(s).

- Hence, one domain of knowing claims or given and then holds onto superiority and asserts the view that “they” with that way of knowing can unilaterally deal with matters at hand. Their judgements and ways of knowing trump all others. Until recently this was precisely what certain kinds of experts/specialists were doing: claiming superior (priestly knowledge) and then teaching (‘doing to’) the public what they considered morally appropriate behaviour or opinion. Post-truth politics is now playing experts at their own game. President Trump’s anti-intellectual stance is a high-profile exemplar of how that counter-game is played. Both sides are engaged in brinkmanship; mirroring the worst sides of each other, in order to win at all costs. Regrettably all that is achieved is an odious impasse and a moral relativism that paralyses public debate and collective wisdom.

So, what has all this got to do with why (some) parents don’t vaccinate their child? The answer is two-fold, firstly, “the facts” are not the primary issue here and when experts continue to try to promote them by stealth of argument they are inadvertently feeding the very real concerns which are the heart of what’s going on: “can we trust what the experts are saying?” The issue at hand is trust, not data. People don’t really care what experts know until they know that they care and they trust them. One way of exhibiting care and deepening trust at this level is to ease off on our institutional imperatives and agendas regardless of the facts at least long enough to facilitate some community building and public deliberation around what the underlying issues and concerns are and creating space for people to build public wisdom around what to do.

Secondly, we need to support the development of more citizen led public narrative around vaccinations, for a deeper discussion on this checkout Marshall Ganz’s work on Public Narrative: Public Narrative, Collective Action, and Power. That process needs to start way back from formal deliberations around vaccinations and other such agendas, with an agenda free investment in community building at neighbourhood level. It’s the convergence of community building and public deliberation that makes all the difference and deepen democracy for the long haul.

Paul Taylor wrote a great post, Why People Hate Your Latest Idea last week, on people’s reaction to “Amazon’s announcement that they’ll soon offer ‘in-home’ delivery — letting couriers literally unlock your front door”.

In the same post he notes:

“Let’s remember that people once thought coffee would make you sterile, train travel would give you a nosebleed, telephones would melt our brains and tractors would lead to the extinction of horses.”

Paul is savvy enough to know that these trends emerge not because people are innately unwise, indeed few have done more in the Housing sector than Paul has done to promote the idea that people and their communities must be valued and humbly served. He is making another point completely, but the statement did make me think about all the folks who do harbour very significant doubt about the value of collective knowledge, as distinct from ‘public opinion’ (I suspect in large part their doubts exist because they don’t make a clear enough distinction between the two). In any case, in a world committed to dividing people and stopping them from engaging in deliberative processes and community building it is quite amazing what people will believe in and vote for. It remains important though that we don’t conclude from such beliefs or actions that people are therefore stupid, but rather that the absence of public deliberation is stupefying and its presence is edifying and liberating.

We are at a Cross-roads. Today democracy sits on a knife edge between Post-truth politics and Epistocracy (rule by experts). How we navigate the blade’s edge will dictate not alone how many children are vaccinated but how we inoculate our communities against the rise of Fascism and Totalitarianism. The stakes could not be any higher, but the starting point is as it always has been: it’s time to change the conversation and to weave a new more inclusive story.

Cormac Russell

David Aynsley

Sometimes the experts do know stuff that some people either collectively or individually do not. To follow the vaccinations metaphor, in 1998 a fraudulent research paper was publishes linking the MMR triple vaccine with autism. People in collective groups believed it, went on TV to warn mothers about it and consequently contributed to the deaths of children who could not take the vaccine due to medical reasons and caught the diseases from children whose mothers would not give them the vaccine. The medical profession doubted the research and warned that this would happen. But, they were not believed by people with wrong collective knowledge. So collective knowledge can be as flawed as expert knowledge (accepting that in this case the collective knowledge was derived from what was believed to be expert knowledge). They collectively believed one man in a white coat and collectively disbelieved many others in white coats.

This example reminds me of one of Cormac’s earlier blogs in which he says that there are somethings that only the authorities can do for people; they must get on and do them. There are some things that people need the help of the local authority with; the local authority should help them. And there are some things that people can do for themselves, let them get on with it.

So in the spirit of ABCD perhaps the different types of knowledge can productively co-exist in a context where people are allowed to do what they can for themselves and authorities are expected to and do what the people cannot.

So to go back to the triple MMR vaccine story, was either side more right or wrong than the other? Both sides can claim they were right based on what they “knew” at the time. But what did they actually know?

N.b. Apologies if my summary of the incident is at all erroneous, jus my personal knowledge

Cormac Russell

I agree David! Worth paying some attention to the power deferentials across the three domanins, but yes proportionality across the piste would be most desireable. Therein lies the challenges, me thinks. BW Cormac

Steve Milton

Yes, proportionality is necessary, but who determines the proportions?

Personally, I value the skills of people who have spent their lives acquiring skills and knowledge,. I don’t want my local community removing my appendix or pulling out my teeth. I don’t take my car to a vet when it is misfiring .

Seems to me sensible to embrace and value the skills, gifts and knowledge all people hold. And that is why I read articles about ABCD written by academic experts..

I think our main problem is the value we attach to different skills and the disproportionate amount of power held by some in society.

Sue Northrop

Cormac, thanks for this. The Faculty for the Psychology of Older People had stories as its conference theme – stories we tell ourselves as psychologists, stories of the people we connect with, it was a very powerful way of understanding what we do and how it works. Narratives and stories are big in dementia thinking and practice, and I use it quite deliberately to create and weave shared stories. Some threads are hard for me and go against my values and all I believe, but I have to accept them and I have to disregard my power over other stories, as by bringing them together we learn and create something of greater value than what I think. Thanks for sharing.