Universal Unconditional Basic Income (Part 1 of 2)

Most owners of capital love production without employment. Yet claim to be surprised when people with limited capital say they’d love income without work (or at least the mind numbing alienating kind).

Bullshit Jobs?

David Graeber in his latest book Bullshit Jobs notes that John Maynard Keynes 1930’s prediction that technological advances would increase leisure time by reducing work to a 15-hour week. Not alone has this not happened, but the very reverse seems to be the case, we are busier than ever. Not just that, but we have, Graeber argues, also seen a significant increase in ass-covers, risk avoiders, and box-tickers.

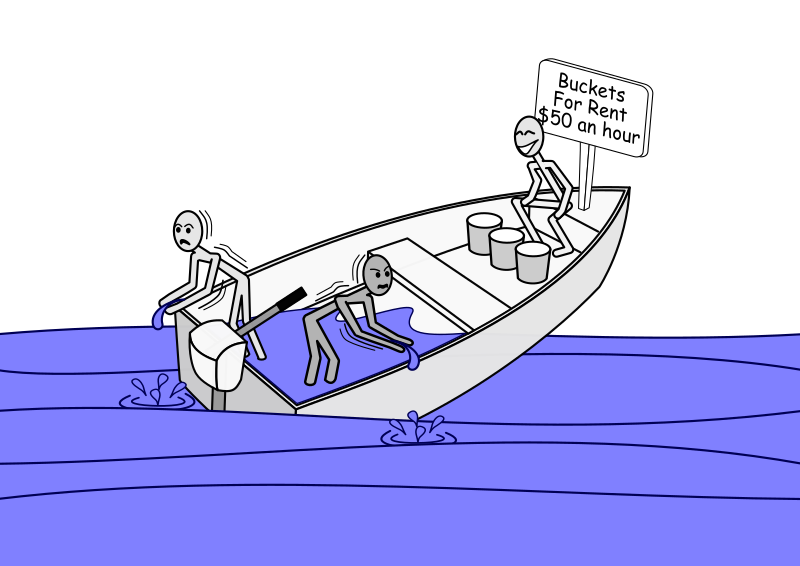

Graeber wonders why it is that capitalist institutions that prize efficiency, measurability and scalability, not to mention value for money, permit so many faux jobs, the likes of which abounded within the bureaucracies of the old Soviet Union. Clearly if its not an economic strategy, he argues, it must be a political one; the prevention of revolt is what he believes to be at the heart of the rise of Bullshit Jobs.

People work to contribute, to find meaning and make a difference. Therefore expecting people to do things that deep-down they feel are inauthentic or unnecessary is traumatising and dehumanising. At the macro level Graeber’s thesis paints a picture of a society that has lost its way and forgotten it primary functions: to enable citizens to co-create shared visions of preferred futures, and to be the primary producers in making those visions, visible and tangible. Graeber proposes a number of solutions to navigate our way out of this modern malaise, chief among them is: Universal unconditional Basic Citizen income.

It seems though that most states would rather sustain bullshit jobs or current welfare programmes, than support Universal Unconditional Basic Income. There are many arguments for and against basic income not to mention reform of welfare systems. All that said our attitudes with regards to how people are ‘valued’ in society lay hidden behind most if not all of those viewpoints. When for example we believe that people’s ‘value’ is derived from their employment status, I think we naturally struggle with the idea of giving people a Basic Income, since most likely we’d see it as giving them ‘money for nothing’. Our fear of doing so (when we hold such beliefs about how people derive their value or how we value people) is that it will promote laziness, or fecklessness.

I make this point simply to highlight that before we can advance a coherent debate about Universal unconditional basic Income, we need to first ask those engaged in such debates how they think people contribute to society and how we can collectively best support such contributions.

When we start the conversation around contribution, and intentionally shift away from market language – including the word ‘value’ which is also an economic trap, we open up a new conversation in the realm of abundance; not scarcity. As we touched on here (Scarcity & remembering the obvious.) two weeks ago, current economic debates are shrouded in the shawl of scarcity. Take again as a case in point the word ‘value’.

You may say ‘I value my children’. But if I were to ask you ‘how much?’, I suspect you’d be lost for words, because it is a grotesque question. After all, we are not talking about something that can be weighed and measured, when we speak about our relationships in such ways. Yet the marketplace insinuates itself in such subtle ways into our everyday lives and in how we express ourselves, that before we know it, we are talking about people as if they were commodities, or units of production and consumption.

However, when the conversation shifts towards gifts, sharing and trust, and away from worth and values, the conversation is transformed and relocated: out of the marketplace/workplace and back into community life.

Of course, in many rural communities in the Global South, the marketplace is still mostly rooted in community life – they are co-terminus and mutually reinforcing, but only because the economy is subordinate to society. The market happens every Wednesday and Friday. Never on the Sabbath or the relevant day of religious observance. The point being made here relates to proportionality between society and economy; not an ounce of theological exegesis is to be found here.

As I’ve said above, while such proportionality is still observable in many rural villages in the Global South, in most of the rest of the world the economy has become dis-embedded (see Karl Polyani – The Great Transformation for a full and authoritative discussion ) from the village and in turn has begun to marginalise communities and their gift exchanges, turning citizens into supplicant consumers and societies into monocultural economies. Indeed with every passing year I notice even in the main cities of the Global South that I visit, that society plays second fiddle to the economy.

The argument for paid jobs, whether we’re telling people to get one or we’re demand the state create more of them is leading us up a cul-de-sac, we need to back up and ask what is all this for? Next week I will build on this reflection and attempt to set out five key questions to help us reboot our societies and re-embed our economies and our lives together.

Cormac Russell

Bill Posters

Excellent Article. It’s a refreshing view point